Worship · February 23, 2023

Frederick Buechner: Tattoo Artist

Scroll through this new exhibit (now on view in the Chesnut Gallery) from the Arts & Our Faith Committee.

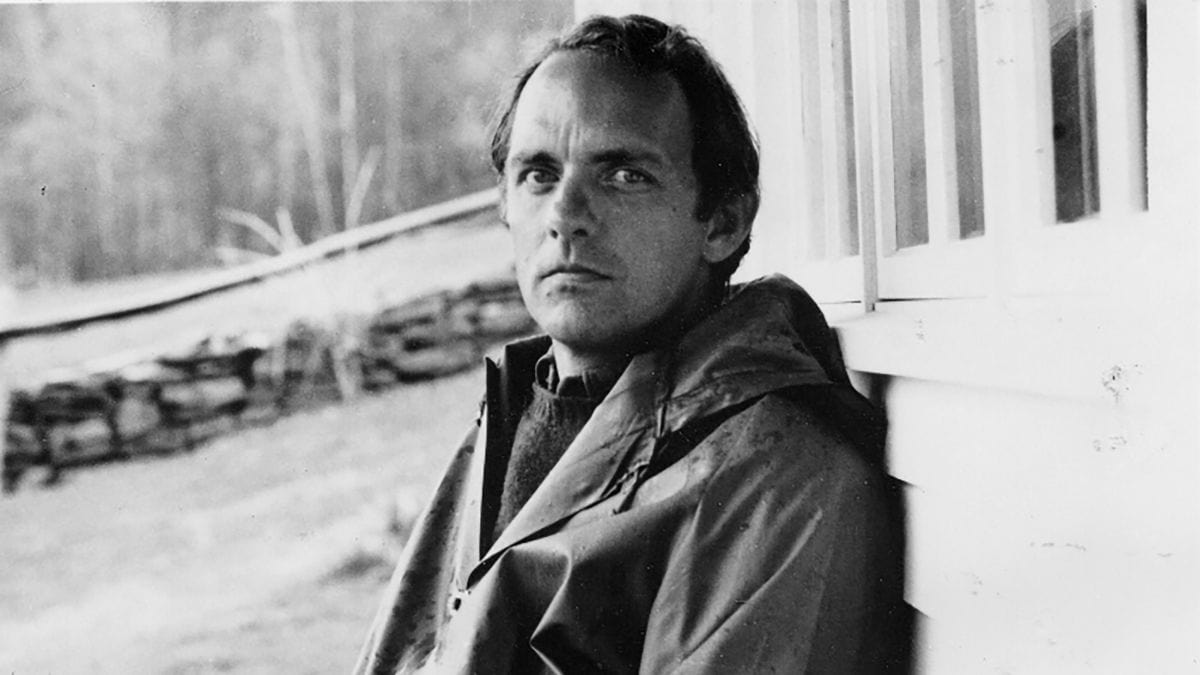

This past summer, the Christian faith lost one of its greatest expositors—Frederick Buechner.

A native New Yorker, Buechner was a Presbyterian pastor, a poet, a professor, a novelist, an essayist and a memoirist. The author of 39 books, he was a finalist for both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize.

The man could write. And what he wrote about, mostly, was Christianity.

“My job, as I saw it, was to defend the Christian faith against its ‘cultured despisers,’” he once said. “To put it more positively, it was to present the faith as appealingly, honestly, relevantly and skillfully as I could.” The challenge, he confessed, was that the language of our faith periodically becomes threadbare.

“There was a time when such words as faith, sin, redemption and atonement had great depth of meaning, great reality; but through centuries of handling and mishandling they have tended to become such empty banalities that just the mention of them is apt to turn people’s minds off like a switch,” he wrote.

Still, “I keep on speaking the language of the Christian faith because, although the words themselves may well be mostly dead, the longer I use them, the more convinced I become that the realities that the words point to are very real and un-dead, and because I do not happen to know any other language that for me points to these realities so well.” (Peculiar Treasures, 1966)

This Lent, we begin a sermon series titled Tattoo: Faith’s Essential Vocabulary. Each week, we will take on some of Christianity’s most challenging ideas, such as Glory, Sin and Spirit. Our aim is to reinvigorate the language of our faith, to distill the essence of each idea and digest it so thoroughly as to leave tattoos on our hearts.

“Buechner was known as a preacher to preachers,” says Senior Pastor Scott Black Johnston. “You could always rely on him for an illuminating story or evocative image that would crystallize a core truth. What better person to help us flesh out this sermon series?”

This exhibit offers Buechner’s thoughts on many of the Christian tenets we will be wrestling with from Ash Wednesday until Easter. We invite you to learn more about Buechner, and immerse yourself in his thinking, at frederickbuechner.com.

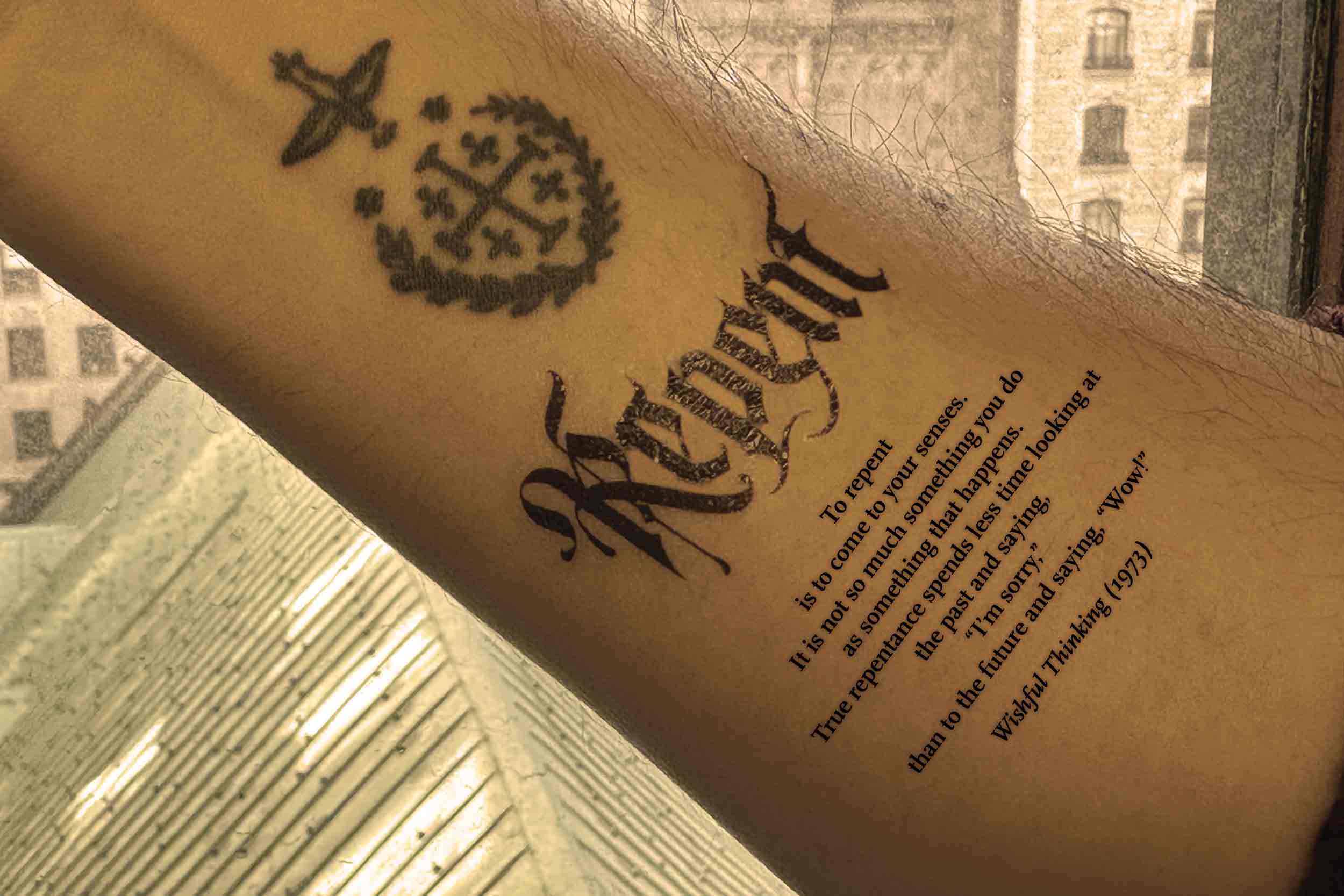

To repent

is to come to your senses.

It is not so much something you do

as something that happens.

True repentance spends less time looking at the past and saying,

“I’m sorry,”

than to the future and saying, “Wow!”

Wishful Thinking (1973)

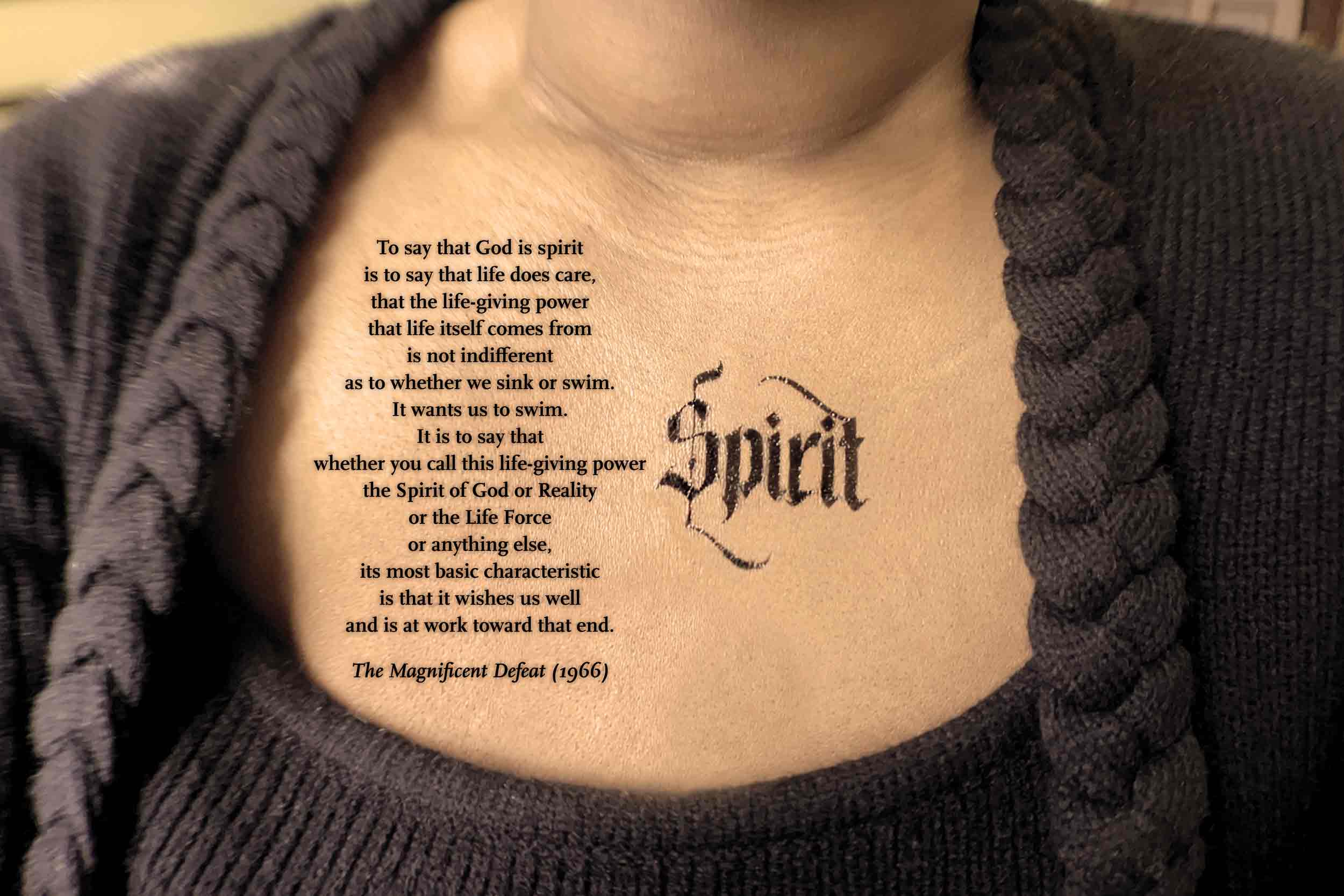

To say that God is spirit

is to say that life does care,

that the life-giving power

that life itself comes from

is not indifferent

as to whether we sink or swim.

It wants us to swim.

It is to say that

whether you call this life-giving power

the Spirit of God or Reality

or the Life Force

or anything else,

its most basic characteristic

is that it wishes us well

and is at work toward that end.

The Magnificent Defeat (1966)

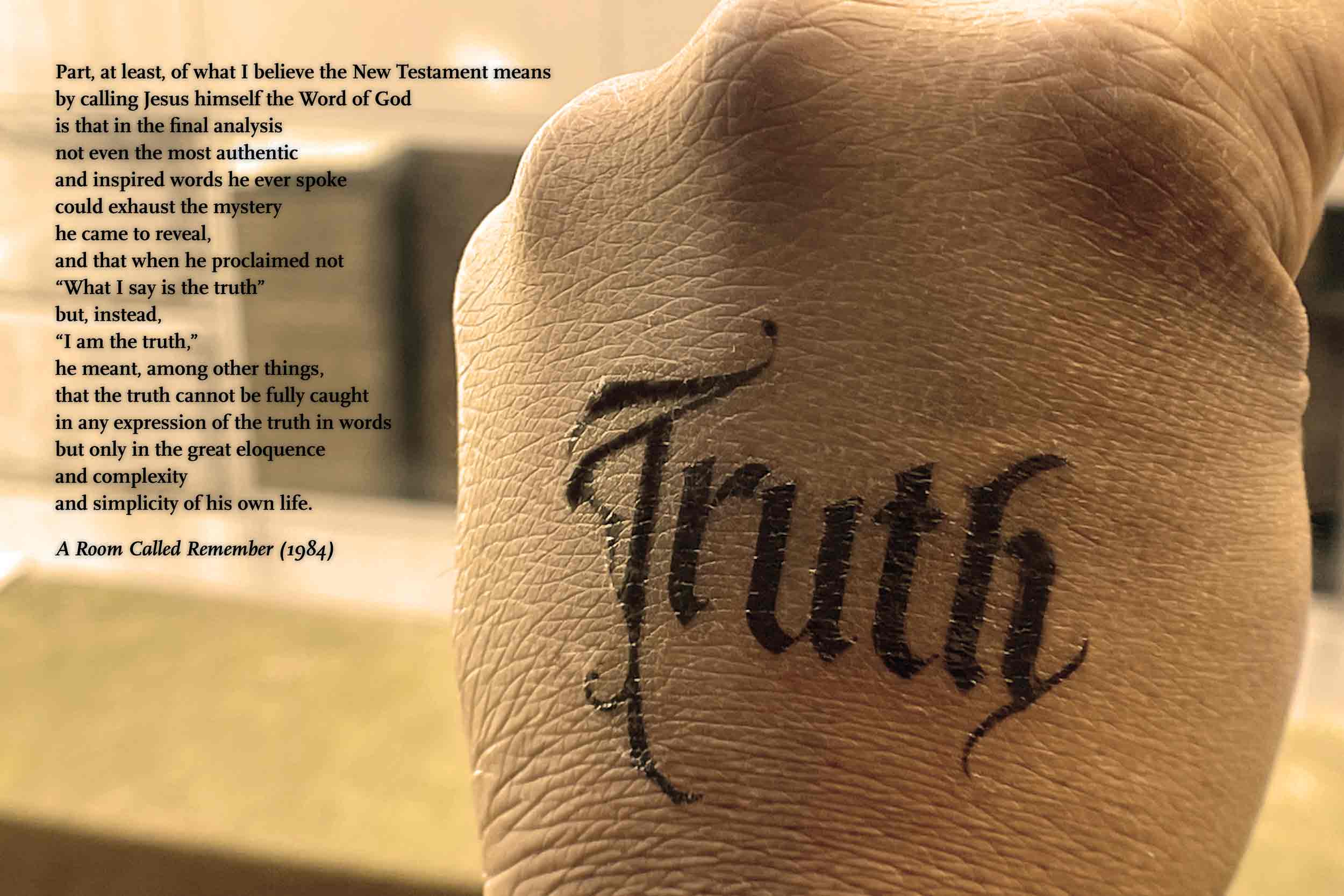

Part, at least, of what I believe the New Testament means

by calling Jesus himself the Word of God

is that in the final analysis

not even the most authentic

and inspired words he ever spoke

could exhaust the mystery

he came to reveal,

and that when he proclaimed not

“What I say is the truth”

but, instead,

“I am the truth,”

he meant, among other things,

that the truth cannot be fully caught

in any expression of the truth in words

but only in the great eloquence

and complexity

and simplicity of his own life.

A Room Called Remember (1984)

The power of sin is centrifugal.

When at work in a human life,

it tends to push everything out toward the periphery.

Bits and pieces go flying off

until only the core is left.

Eventually bits and pieces of the core itself go flying off

until in the end nothing at all is left.

“The wages of sin is death”

is Saint Paul’s way of saying the same thing.

Original sin means we all originate out of a sinful world,

which taints us from the word go.

We all tend to make ourselves the center of the universe, pushing away centrifugally from that center

everything that seems to impede its freewheeling.

More even than hunger, poverty, or disease,

it is what Jesus said he came to save the world from.

Wishful Thinking (1973)

Glory is to God what style is to an artist.

A painting by Vermeer,

a sonnet by Donne, a Mozart aria

each is so rich with the style of the one who made it that to the connoisseur

it couldn’t have been made by anybody else,

and the effect is staggering.

In the words of Psalm 19:1,

“The heavens are telling the glory of God.”

It is the same thing.

To the connoisseur,

not just sunsets and starry nights,

but dust storms, rain forests,

garter snakes, and the human face

are all unmistakably

the work of a single hand.

Glory is the outward manifestation

of that hand in its handiwork

just as holiness is the inward.

To behold God’s glory, to sense God’s style,

is the closest you can get to God this side of paradise, just as to read King Lear

is the closest you can get to Shakespeare.

Glory is what God looks like

when for the time being

all you have to look at him with

is a pair of eyes.

Wishful Thinking (1973)

The final secret, I think, is this:

that the words

“You shall love the Lord your God”

become in the end

less a command than a promise.

And the promise is that, yes,

on the weary feet of faith

and the fragile wings of hope,

we will come to love him at last

as from the first he has loved us—

loved us even in the wilderness,

especially in the wilderness,

because he has been in the wilderness

with us.

“And these words

which I command you this day

shall be upon your heart,

and you shall teach them diligently

to your children,

and you shall talk of them

when you sit in your house,

and when you walk by the way,

and when you rise.”

And rise we shall, out of the wilderness,

every last one of us,

even as out of the wilderness

Christ rose before us.

That is the promise,

and the greatest of all promises.

A Room Called Remember (1984)

It comes from the Latin vocare, to call,

and means the work a man is called to by God.

There are all different kinds of voices

calling you to all different kinds of work,

and the problem is

to find out which is the voice of God

rather than of Society, say,

or the Super-ego, or Self-Interest.

By and large a good rule for finding out is this.

The kind of work God usually calls you to

is the kind of work

(a) that you need most to do and

(b) that the world most needs to have done.

The place God calls you to

is the place where your deep gladness

and the world’s deep hunger meet.

Wishful Thinking (1973)

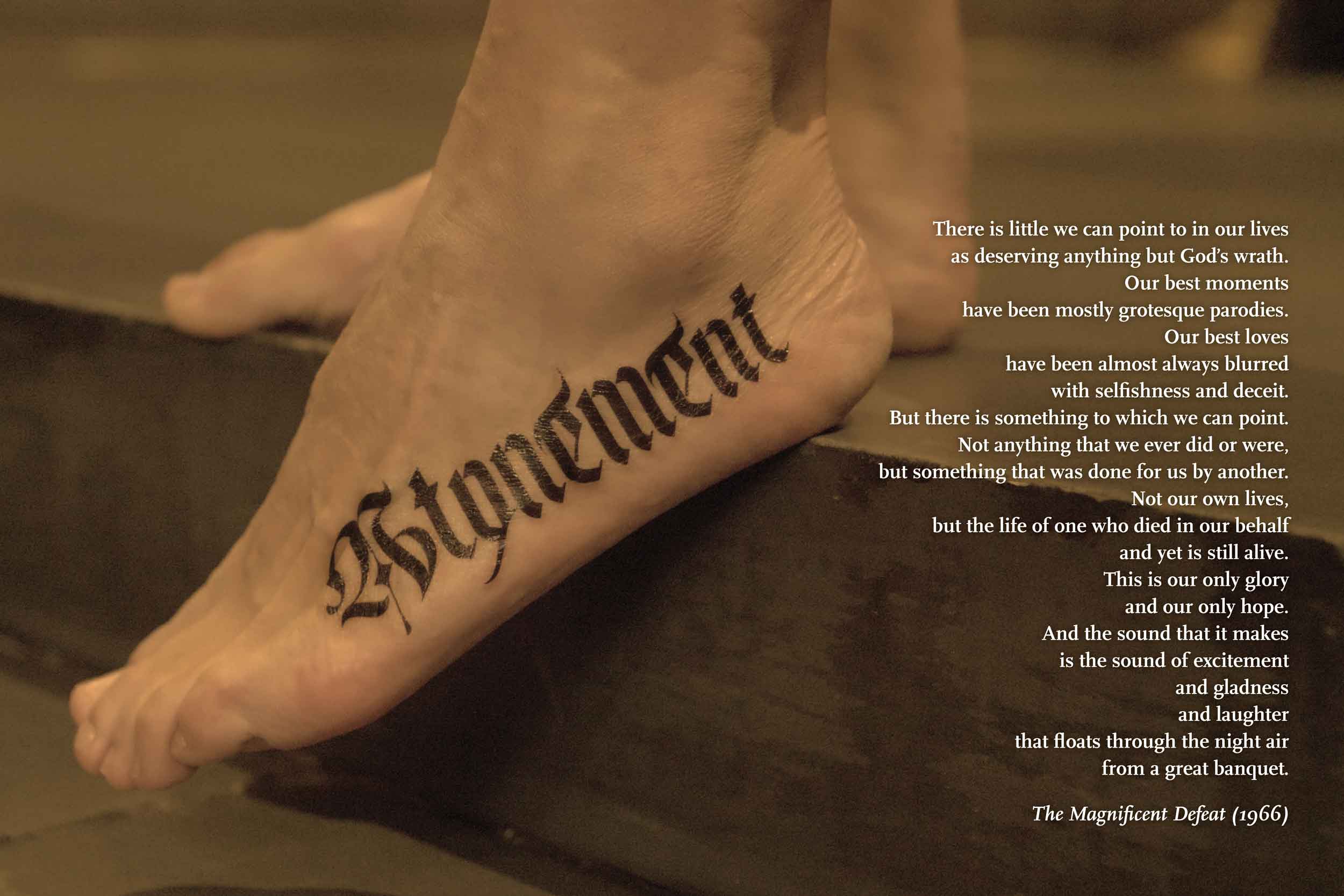

There is little we can point to in our lives

as deserving anything but God’s wrath.

Our best moments

have been mostly grotesque parodies.

Our best loves

have been almost always blurred

with selfishness and deceit.

But there is something to which we can point.

Not anything that we ever did or were,

but something that was done for us by another.

Not our own lives,

but the life of one who died in our behalf

and yet is still alive.

This is our only glory

and our only hope.

And the sound that it makes

is the sound of excitement

and gladness

and laughter

that floats through the night air

from a great banquet.

The Magnificent Defeat (1966)

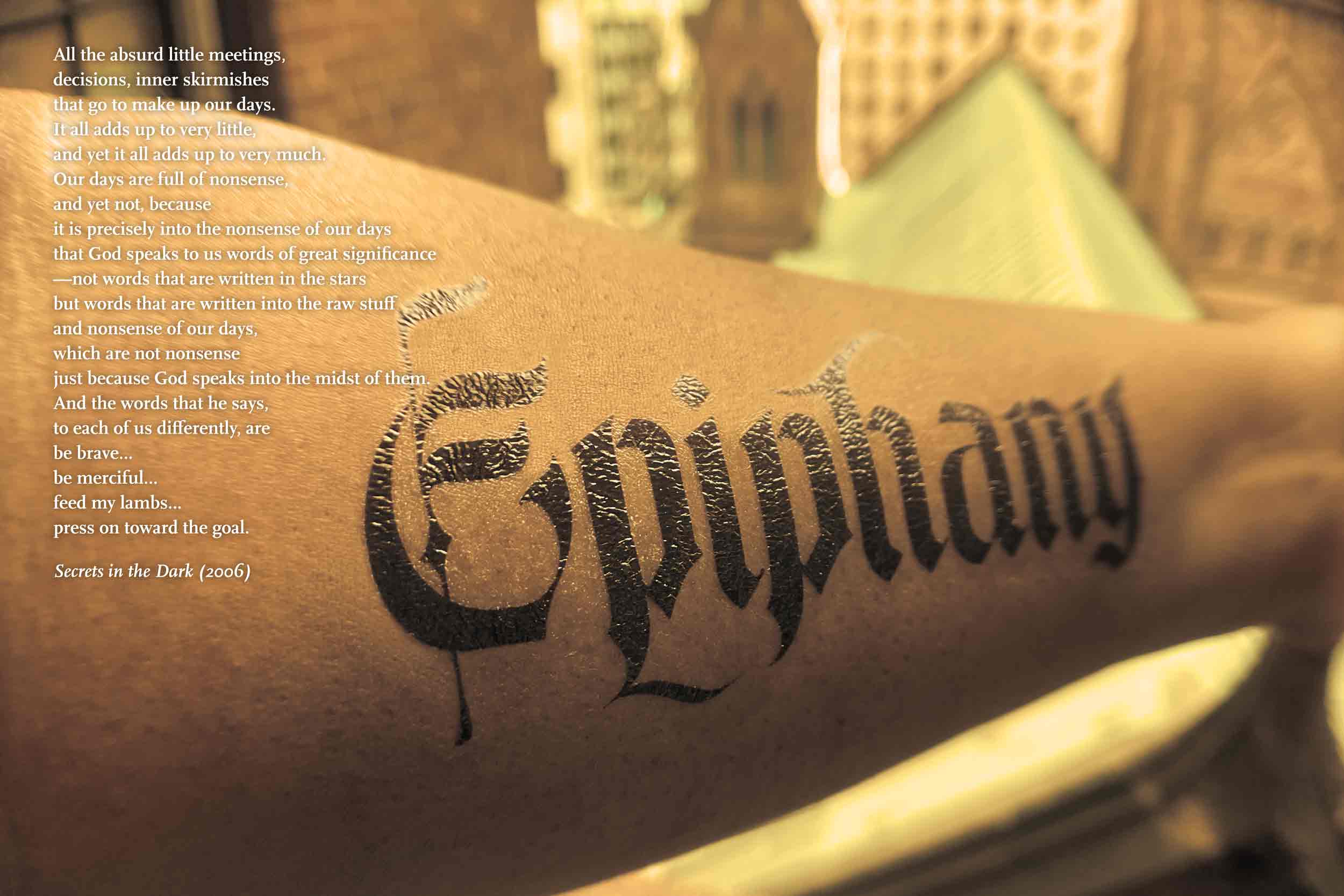

All the absurd little meetings,

decisions, inner skirmishes

that go to make up our days.

It all adds up to very little,

and yet it all adds up to very much.

Our days are full of nonsense,

and yet not, because

it is precisely into the nonsense of our days

that God speaks to us words of great significance

—not words that are written in the stars

but words that are written into the raw stuff

and nonsense of our days,

which are not nonsense

just because God speaks into the midst of them.

And the words that he says,

to each of us differently, are

be brave…

be merciful…

feed my lambs…

press on toward the goal.

Secrets in the Dark (2006)

This exhibit is sponsored by the Arts & Our Faith Committee.

Photography and design by Vasheena Brisbane.