General News · May 8, 2023

Seeing Betsey, at Last

On Sunday, May 21, Fifth Avenue Presbyterian will unveil a portrait of Betsey Jackson, one of the founding members of this congregation. We have no idea what Betsey Jackson looked like—but that didn't stop us.

Who Was Betsey Jackson?

Everything we know (or think we know) about Betsey Jackson can be told in a single paragraph.

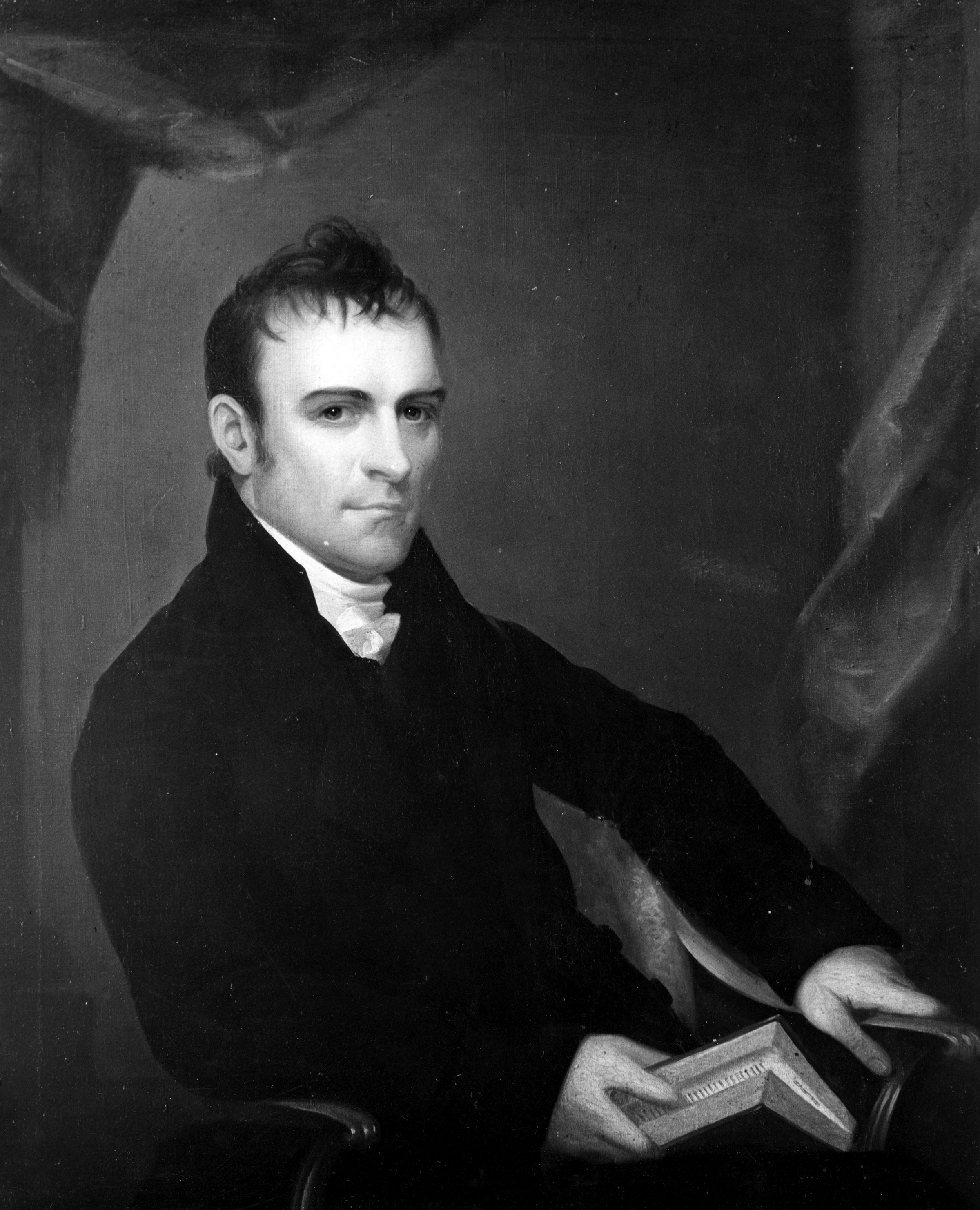

She was born around 1782 and lived in Albany, New York, where she was one of two enslaved persons in the household of the Rev. Dr. John B. Romeyn. In 1808, she moved with the household to Manhattan, where Dr. Romeyn became the first pastor of the Cedar Street Presbyterian Church. She was one of the 26 founding members of the congregation that would later become Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church. Session records indicate that she got crossways with two fellow members of the congregation but promised to repent. Dr. Romeyn granted her emancipation in 1811. She died on Aug. 31, 1822, at about age 40.

Even gathering that amount of detail has been painstaking. In the records listing our founding members, her name always came last: “Betsey Jackson, household slave.” We knew little else, though the church took pride in the fact that an African American enslaved woman had been accepted into full membership two decades before slavery officially ended in the state of New York.

A breakthrough came in 2018, when John Jay College released its New York Slavery Records Index. There it was: a manumission record for Elizabeth Jackson, signed by John B. Romeyn. It read in part, “Elizabeth shall, and may at all times hereafter, exercise, hold and enjoy, all and singular, the liberties, rights, privileges and immunities of a free woman, fully to all intents and purposes as if she had been born free.”

Senior Pastor Scott Black Johnston appointed a task force to consider how Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church should reckon with this troubling aspect of our history. The task force responded with a slate of recommendations that said, in essence, that we can no longer remember John Romeyn without remembering Betsey Jackson.

On Sunday, May 21, next door to the Romeyn Room on the fifth floor of the church house, Fifth Avenue will dedicate the Betsey Jackson Board Room. A portrait of John Romeyn will remain in the Romeyn Room. And in the Betsey Jackson Board Room, we will unveil a newly commissioned portrait of our 26th founding member.

The portrait was the senior pastor’s idea, a way to balance our recognition of Romeyn with our recognition of Jackson. The fact that no likenesses of Betsey Jackson exist did not deter him.

“People have been painting Jesus and other Biblical figures for millennia,’ he says. “Artists have created literally millions of depictions of Christ. The oldest painting that we have of Jesus is from about 235 CE. Needless to say, none of those artists were working from a photograph. They were working from their faithful imagination, and that is exactly what we wanted an artist to do in painting Betsey Jackson.”

Imagining Betsey

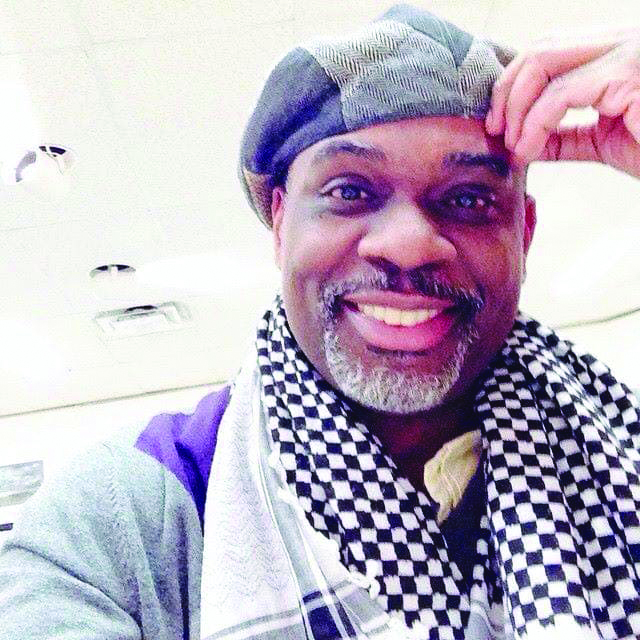

“What must life have been for her? How does one navigate that?” Clayton Singleton wonders. “What type of tenacity, courage and respect must this person have had? I was totally intrigued.”

Singleton, a portrait artist in Norfolk, Virginia, is the man who was tasked with bringing Betsey Jackson to life on canvas. In addition to painting, Singleton is a full-time teacher and sometimes-actor who grew up among people who were “always creating, always educating, really trying to move throughout our Norfolk society and just grow.”

Singleton drew on his roots and his Norfolk connections to help him envision who Betsey Jackson might have been. Fellow teachers, actors and other theater people all had a hand in the process.

“I sent them the information you all had sent to me about Betsey,” he says. “Instantly they all started talking back to me. They started doing their own research. Then it was, ‘I know a person who does costumes. I know a hair and makeup person.’”

He still needed a model. He’d once performed in a production of The Colored Museum (a play by George C. Wolfe) with a local actress and retired teacher named Pinkie Chapelle. She wasn’t exactly the right age, but she had the tenacity and steel that Singleton imagined Betsey shared.

“Pinkie said she loved the idea and asked me what did I need from her,” he recalls. “I said I just need you to show up and be who you are.”

The Portrait Comes to Life

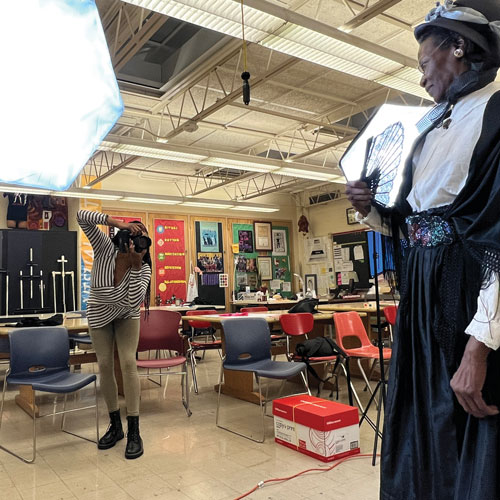

On Nov. 10 last year, Singleton and his crew—Chapelle; photographer Kristen Singleton (no relation); costumer Staci Murawski; and facilitator Jenae Thompson—met in his studio to recreate Betsey Jackson from head to toe.

For Murawski, it was a virtual meeting. She had assembled 10 historically accurate outfits—shoes, shawls, belts, corsets, even undergarments—and worked with Chapelle via FaceTime to put them together.

Once Chapelle was dressed, Kristen Singleton picked up her camera.

“It was a wonderful experience to have everyone come together, to bring their expertise, their ideas, their passion for who we were attempting to embody,” Singleton says. “You could feel the love, feel the respect in the room.”

Even when he is working with a contemporary subject, Singleton works from photographs. He pores over the images to find the expressions and attitudes that match his own impressions of the individual. With Betsey Jackson, one particular image of Chapelle resonated.

“That expression on her face carried the weight of her life, yet it still had hope in it,” he says. “That facial expression totally sat with me.”

He took that image along with two others and uploaded them to Photoshop. “I edited them until I got to one version, and I thought, ‘That’s the one.’ [Betsey] was just looking at me like, ‘Here I am.’”

The events commemorating Betsey Jackson begin at 12:30 pm Sunday, May 21, in Bonnell Hall.