Music + Arts · March 30, 2020

The Story Behind That Remarkable Choir Video

It all started with a Zoom call (where else?).

Ryan Jackson was brainstorming with members of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church choir about how—in a time of lockdown and distancing—they could still contribute to Sunday worship.

The church suspended live Sunday worship on March 12, and for the last three weeks has created a half-hour video to share with the congregation. Each of the four pastors records segments of the service by themselves, either from home or from church. For the first two weeks, Ryan and a few individual choir members met to record solos. But larger gatherings of choristers were impossible.

Until this week. As the video for the Fifth Sunday in Lent came to a close, viewers saw and heard something remarkable.

It may look at first like a Zoom call—that now-ubiquitous checkerboard of faces—but the 90-second performance of Barry Peters’ “A Celtic Prayer” is in fact a compilation of 22 video and audio files, each recorded separately, then artfully blended to sound just as we would hear it cascading from the organ loft on a Sunday morning.

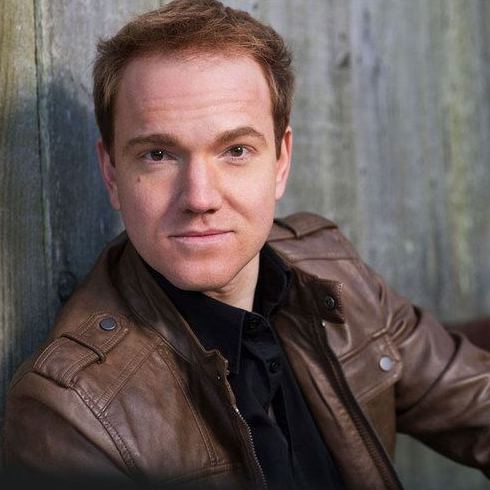

Credit Ryan with the idea. Credit choir member Jonathan Estabrooks with the execution—all 20-plus hours of it.

“In addition to singing in the choir, I have a video production company, and I do a lot of different projects,” Jonathan says. “But I have never done a virtual choir project like this.”

The first challenge was how to amass all of the shots, each recorded in different places with varying levels of technology. Ryan began by recording a guide track and conducting video, which included scrolling music for the singers. That file went out to all the choir members so that they could listen, follow Ryan’s direction and record themselves singing their individual parts. Jonathan coached them on best practices (face a window for the best lighting, shoot in landscape mode) to get a clean video and acceptable audio from their smartphones.

‘We had to contend with kids and outside construction noise in a few cases,” he says, “but within a week all the files were uploaded to Google.” He dropped the files into an editing program, then started working on the sound. He eyeballed the visual waveforms of each file to align the opening notes and continued from there.

“Even with the conductor’s guide, there were many variations in tempo and keys,” he says. “When you are singing by yourself, instead of beside a singer partner, even with professional musicians it’s not always possible to be as precise as in a live scenario. I had to really dig in and work on ends of phrases and breaths. There is certainly more need for perfection in a project like this. Video is forever, and we tend to listen more intently and more often to online content. Cue my perfectionist streak.”

Even more time consuming was the video. Jonathan labored over color corrections to create a consistent tone across the sea of faces. Rather than freeze the image there, he panned over the faces to mimic the look and feel of a three-dimensional performance. The performance begins with a soprano lead line, but as the video sweeps over the lower quarter of the screen, a stronger bass line emerges. Listening carefully, you can even discern individual voices, just as you might at a live performance.

“I knew I wanted to zoom in and out and move the camera around,” Jonathan says. “So I exported one large video image, then I was able to go in and animate the camera moves. I added some filters to stylize it and give it some visual interest. Video painting so to speak.”

Jonathan and Ryan completed “A Celtic Prayer” on Saturday, and videographer Emily Dombroff appended it to the Sunday worship video. It appears after the pastor’s benediction, at the moment during a live service when the choir would sing the Choral Response (just before the congregation exits the pews). Surely no one watching online was expecting a choral farewell anything like what followed Charlene Han Powell’s blessing.

“The choral response at the very end blew me away,” one viewer said in an email. Another wrote, “I thank Ryan and his choir. That last scan of all those dear faces brought me to tears.”

The segment also caught the eye of a fellow Presbyterian in Wooster, Ohio. A member of First Presbyterian inquired, “I was wondering if you would be willing to discuss with me how exactly you were able to recording all of the members of your choir and add them to your digital service? The synchronization was extremely impressive and I would like to emulate the product within our own service.”

Jonathan’s work as a videographer is heavily connected with music. When is he not performing with the Fifth Avenue choir or pursuing his soloist career, he is producing music videos, behind-the-scenes mini-docs about artists and their music, and large charity projects. He is currently working on his first feature-length documentary on the first generation of African American opera legends. BLACK OPERA will tell the stories of Jessye Norman, Leontyne Price, George Shirley and three more groundbreaking performers of the mid-20th century.

Jonathan has been a member of the Fifth Avenue choir for two years. A Canadian, he first met Ryan when both were undergraduates at the University of Toronto. He auditioned and won a spot in the choir not long after the two reconnected at The Juilliard School.

“It was a painstaking process, but it was worth it to see my friends’ smiling faces,” Jonathan says of “A Celtic Prayer.” “It made us feel better to do something for the congregation. We certainly miss all of them. If there is a silver lining to what we are all living through, it’s that it creates a space for creativity, ingenuity and thinking outside the box. That’s what made this video possible. We are all just doing what we can to continue connecting by sharing our art and our music.”